Over the years, I’ve come to rely on weather information just like most of us who live along the Gulf Coast. Whether it’s getting ready for a hurricane or figuring out if a quick shower will interrupt weekend plans, accurate hurricane prediction and forecasting can be a lifesaver. But lately, I’ve noticed a frustrating trend—meteorologists and even amateur weather enthusiasts have become more and more eager to share hurricane predictions before a storm has even formed.

Over the years, I’ve come to rely on weather information just like most of us who live along the Gulf Coast. Whether it’s getting ready for a hurricane or figuring out if a quick shower will interrupt weekend plans, accurate hurricane prediction and forecasting can be a lifesaver. But lately, I’ve noticed a frustrating trend—meteorologists and even amateur weather enthusiasts have become more and more eager to share hurricane predictions before a storm has even formed.

This wouldn’t be a big deal if these early predictions were accurate, but more often than not, they aren’t. What’s worse, I’ve noticed how social media pages, news outlets like Fox 8, and even some reputable hurricane tracker sites start showing where a storm might land—sometimes a week out—before there’s even a center of circulation. The problem is that even once we do get a well-formed storm, predicting its path three days out is still a challenge.

So, what’s going on here? Why are we getting storm forecasts so early, and why do they cause more harm than good?

How Hurricane Tracker Sites and Early Predictions Have Taken Over

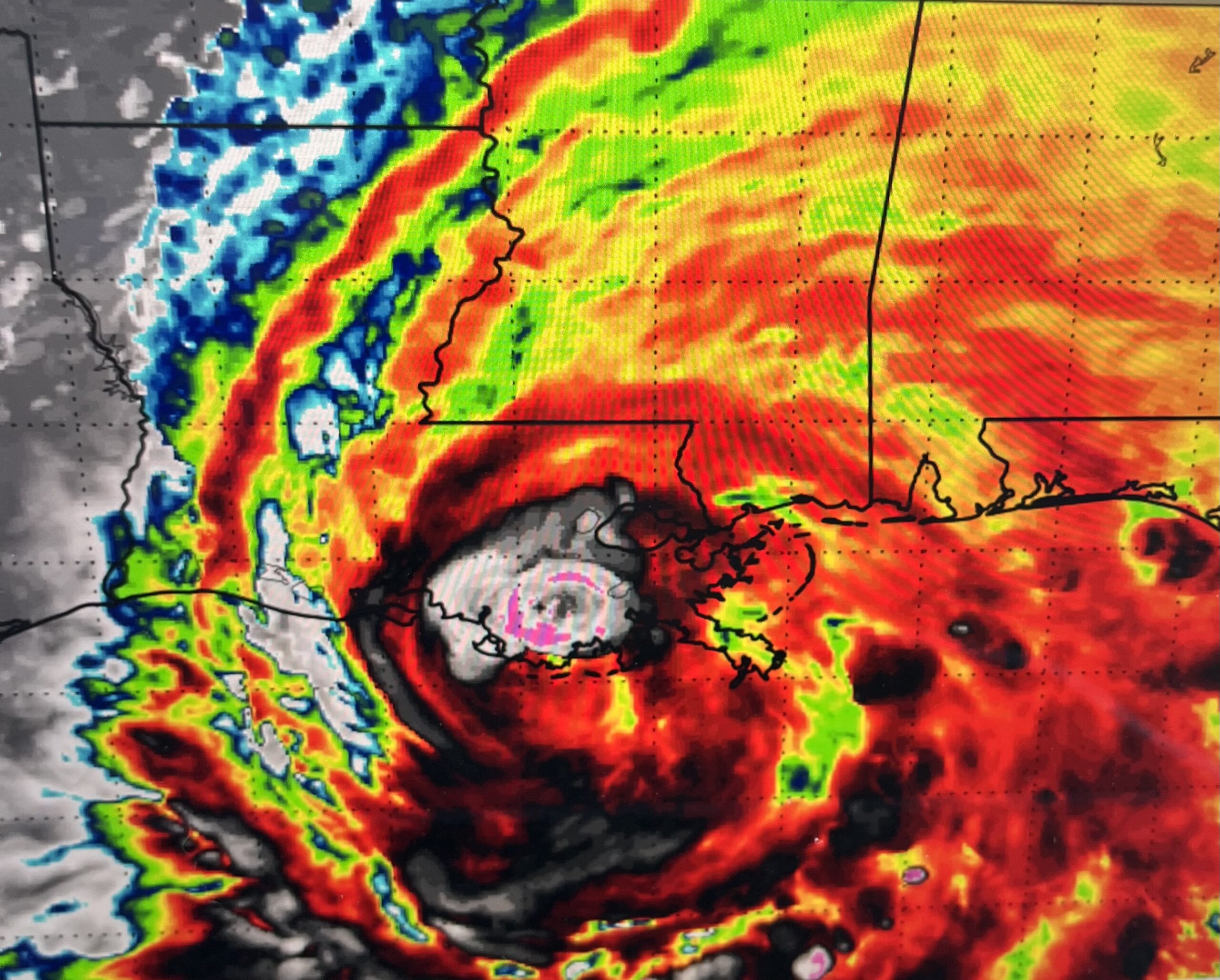

If you’ve followed hurricane tracker tools for severe weather, you’ve probably seen how advanced our tools have become. Today, we have satellite imagery, Doppler radar, and highly sophisticated models like the GFS (Global Forecast System) and the European ECMWF. These models are constantly updated to show us possible storm formations, and in many cases, they’ve been able to give us a few extra days’ notice.

Sounds great, right? Well, not so fast. While we can often spot the “potential” for a hurricane to form, that’s where things get tricky. I’ve been following Fox 8 meteorologist Zack Fradella and a few other local forecasters, and I’ve noticed that they (and others on social media) will often predict a storm’s potential days before it actually forms. In the last week alone, there was constant chatter about a storm forming in the northwest Caribbean Sea, and Louisiana was the primary target.

But here we are—a week later—and that storm still hasn’t formed. Now, they’re shifting their predictions east toward Alabama and Florida. The kicker? We’re still waiting for this storm to actually exist. It’s not the first time this has happened, either. And every time it does, I feel like it just adds to the confusion and the unnecessary stress of not knowing what to believe.

Why Premature Predictions of Severe Weather Are a Problem

One of the biggest issues with these premature predictions is that they often make people nervous for no reason. Look, I understand that we want as much lead time as possible to prepare for hurricanes, but when you start seeing maps showing potential landfall locations before a storm even exists, it feels more like guesswork than science.

Let me give you a recent example. A few days ago, Facebook pages dedicated to weather information started sharing models showing a storm heading toward Louisiana. This was almost a full week before anything had formed in the northwest Caribbean Sea. Everyone was talking about how Louisiana was going to be hit, and people started to get concerned—should they prepare, or should they wait? And now, a week later, the models are showing the storm hitting farther east, near Alabama or Florida, but it still hasn’t even formed yet.

This constant back and forth just makes it harder for people to trust these forecasts. In fact, I’ve noticed a lot of folks are starting to get fatigued by these early warnings that never seem to pan out. How many times can we be told a storm is coming, only to watch it fizzle out or shift direction, before we stop believing the warnings altogether?

The Challenges of Using Weather Satellite Data for Hurricane Prediction

Now, I don’t want to come across as someone who doesn’t respect the science of meteorology. Far from it. Predicting hurricanes is hard—really hard. Even when a storm finally forms and gets a defined center of circulation, meteorologists still have to deal with a lot of unpredictable factors that can make their jobs difficult.

For instance, hurricanes are influenced by atmospheric pressure systems, wind shear, and sea surface temperatures. Any small change in one of these variables can cause the storm to shift direction or lose strength, sometimes without much warning. A high-pressure ridge might steer a storm west, while a low-pressure trough can send it curving north. Wind shear can weaken a storm or cause it to drift off course. And then there’s the interaction with land, which can slow down or weaken a hurricane, but predicting exactly when that happens is still tricky.

Even with all the advancements in technology, including weather satellites, predicting a hurricane’s exact path and intensity is still a game of probabilities. And that’s where we see the “cone of uncertainty”—that infamous forecast map that shows where the storm might go. But even then, the storm’s impact can extend far outside the cone, and it’s not unusual to see forecasts change dramatically, even within 48 hours.

The Impact on Public Trust in Hurricane Tracker Tools

I think one of the worst outcomes of this trend is the impact it has on the public’s trust in weather information and hurricane tracker tools. When you’re told about a storm days in advance and given specific landfall predictions, you naturally want to start preparing. But when those predictions change or the storm doesn’t develop, it can feel like a false alarm. After a few of these premature warnings, people start to get jaded. They may even ignore important warnings when a real storm is actually headed their way.

I’ve seen it happen. A storm is hyped up on social media, everyone gets worked up, and then nothing happens. The next time a warning comes around, some folks roll their eyes and think, “Here we go again.” But the danger is that when that storm does come—and the warnings are accurate—people won’t take it as seriously. It’s a risky game to play.

The constant shift in predictions also has a financial impact. How many people rushed to stock up on supplies or prepare their homes based on a week-out forecast, only to find out they didn’t need to? Evacuating too early or prepping unnecessarily can cost money, and when it feels like that effort is wasted, people get frustrated.

Social Media and the Amplification of Hurricane Predictions

A big part of the problem is how quickly information spreads on social media. Weather-related Facebook pages and Twitter accounts are constantly sharing speculative forecasts, often based on early model runs that have a lot of uncertainty. These posts tend to focus on worst-case scenarios because, let’s face it, those are the ones that get the most clicks.

Now, don’t get me wrong—I really enjoy following Zack Fradella’s forecasts, particularly his analysis of the LRC (Lezak’s Recurring Cycle) pattern. His breakdown of this weather pattern offers predictive insights into future weather systems that have a certain rhythm to them, and I can see why Zack seems to have taken a liking to it. I have no doubt that with his talent, we’ll eventually see Zack Fradella as one of our National Hurricane Center forecasters.

That said, even though I appreciate his forecast insights, especially those based on the LRC pattern, I’m still cautious when early predictions circulate that are not yet rooted in hard data from sources like weather satellites. I think we all need to approach these speculative forecasts with a critical eye, particularly when they are amplified across social media without proper context.

Why Premature Predictions of Hurricanes Persist

So, why does this keep happening? Why do we keep seeing premature hurricane predictions when they seem to cause more confusion than clarity? A big reason is that these long-range model predictions are readily available and easy to share. The public has access to the same weather information and models that meteorologists use, and while that’s great for transparency, it also means that people who don’t fully understand the science behind these models are sharing them without the necessary context.

There’s also a demand for early information. I get it—people want as much time as possible to prepare, and they appreciate being told that there’s a potential storm brewing. But there’s a fine line between being informed and being misled. Right now, I think we’re leaning too far toward the latter.

What Needs to Change in Hurricane Prediction

If we want to avoid the confusion and panic that comes with premature hurricane predictions, there are a few things that need to change.

First, I think meteorologists and weather sites need to be more cautious about sharing speculative forecasts. If a storm hasn’t formed yet, there should be a clear disclaimer that the forecast is highly uncertain. Instead of showing maps that predict where a storm might hit a week out, forecasters should focus on general areas where conditions are favorable for storm development, without pinpointing specific locations.

Second, the public needs to be better educated on how to interpret these long-range forecasts. We need to understand that a model run showing a hurricane hitting a particular city a week out is far from a guarantee. It’s simply a possibility, and one that could change significantly over time.

Lastly, I think social media pages need to be more responsible with the content they share. Sensationalism might get more clicks, but it’s also creating unnecessary anxiety and confusion. If you run a weather-focused page, take the time to explain the uncertainty of these early predictions, and don’t focus solely on worst-case scenarios.

Ralph